Last Updated on October 4, 2021 3:52 pm by INDIAN AWAAZ

They get Prize for discoveries of receptors for temperature and touch

WEB DESK

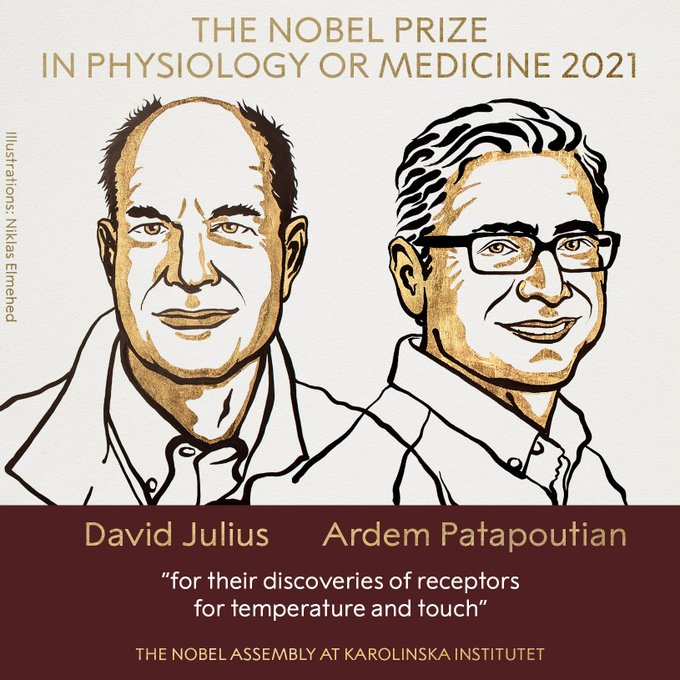

The 2021 #NobelPrize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded jointly to David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian “for their discoveries of receptors for temperature and touch.”

“Our ability to sense heat, cold and touch is essential for survival and underpins our interaction with the world around us. In our daily lives we take these sensations for granted, but how are nerve impulses initiated so that temperature and pressure can be perceived? This question has been solved by this year’s Nobel Prize laureates,” the Nobel Assembly said.

David Julius of the University of California utilised capsaicin, a pungent compound from chili peppers that induces a burning sensation, to identify a sensor in the nerve endings of the skin that responds to heat. Ardem Patapoutian, who is with Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Scripps Research, used pressure-sensitive cells to discover a novel class of sensors that respond to mechanical stimuli in the skin and internal organs.

David Julius was born in 1955 in New York, USA. He received a Ph.D. in 1984 from University of California, Berkeley and was a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University, in New York. David Julius was recruited to the University of California, San Francisco in 1989 where he is now Professor.

Ardem Patapoutian was born in 1967 in Beirut, Lebanon. In his youth, he moved from a war-torn Beirut to Los Angeles, USA and received a Ph.D. in 1996 from California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, USA. He was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, San Francisco. Since 2000, he is a scientist at Scripps Research, La Jolla, California where he is now Professor. He is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator since 2014.

David Julius utilized capsaicin, a pungent compound from chili peppers that induces a burning sensation, to identify a sensor in the nerve endings of the skin that responds to heat. Ardem Patapoutian used pressure-sensitive cells to discover a novel class of sensors that respond to mechanical stimuli in the skin and internal organs. These breakthrough discoveries launched intense research activities leading to a rapid increase in our understanding of how our nervous system senses heat, cold, and mechanical stimuli. The laureates identified critical missing links in our understanding of the complex interplay between our senses and the environment.

How do we perceive the world?

One of the great mysteries facing humanity is the question of how we sense our environment. The mechanisms underlying our senses have triggered our curiosity for thousands of years, for example, how light is detected by the eyes, how sound waves affect our inner ears, and how different chemical compounds interact with receptors in our nose and mouth generating smell and taste. We also have other ways to perceive the world around us. Imagine walking barefoot across a lawn on a hot summer’s day. You can feel the heat of the sun, the caress of the wind, and the individual blades of grass underneath your feet. These impressions of temperature, touch and movement are essential for our adaptation to the constantly changing surrounding.

In the 17th century, the philosopher René Descartes envisioned threads connecting different parts of the skin with the brain. In this way, a foot touching an open flame would send a mechanical signal to the brain (Figure 1). Discoveries later revealed the existence of specialized sensory neurons that register changes in our environment. Joseph Erlanger and Herbert Gasser received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1944 for their discovery of different types of sensory nerve fibers that react to distinct stimuli, for example, in the responses to painful and non-painful touch. Since then, it has been demonstrated that nerve cells are highly specialized for detecting and transducing differing types of stimuli, allowing a nuanced perception of our surroundings; for example, our capacity to feel differences in the texture of surfaces through our fingertips, or our ability to discern both pleasing warmth, and painful heat.

Prior to the discoveries of David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian, our understanding of how the nervous system senses and interprets our environment still contained a fundamental unsolved question: how are temperature and mechanical stimuli converted into electrical impulses in the nervous system?