Last Updated on January 2, 2026 12:53 am by INDIAN AWAAZ

Staff Reporter

The number of communal riots in India declined sharply in 2025, falling by more than half compared to the previous year, according to monitoring data released by the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS). The report recorded 28 communal riot incidents in 2025, down from 59 in 2024, marking a decline of around 52 per cent.

However, the report cautioned that the reduction in large-scale communal violence has not translated into a broader easing of identity-based tensions. While the frequency of riots dropped, incidents of mob lynching showed a marginal increase. In 2025, 14 cases of mob lynching were reported across the country, resulting in eight deaths.

CSSS noted that communal conflict in India appears to be taking new and less visible forms. Instead of street-level violence alone, the report highlighted a rise in institutionalised discrimination, particularly targeting Muslim and Christian communities. It pointed to the increasing prevalence of hate speech, alongside what it described as the forced invisibilisation and marginalisation of Muslim and Christian cultures from public spaces.

Recent attacks on Christmas celebrations in multiple regions of India, reportedly perpetrated by Hindu right-wing groups, as well as sustained campaigns targeting Muslim rulers of the yore and places of worship of minorities, serves as an indicator of communal hostility. Together, these developments underscore a shift from episodic communal riots toward more systemic and normalized forms of communal exclusion and violence.

The year 2025 witnessed a significant escalation in incidents of violence targeting Christian communities across various regions of India. According to data compiled by the United Christian Forum (UCF), a total of 706 incidents of violence against Christians were recorded nationwide as of November 2025. A majority of these attacks were carried out under the pretext of preventing religious conversions, reflecting the growing instrumentalisation of anti-conversion narratives to legitimise coercive and violent actions.

One recurrent and particularly severe form of violence reported during the year involved the denial of burial rights to Christians, especially in tribal-dominated states such as Chhattisgarh. In several instances, state authorities were implicated in the exhumation of Christian bodies, constituting a grave violation of religious freedom and human dignity. UCF documented 23 burial-related incidents in 2025, of which 19 occurred in Chhattisgarh, two in Jharkhand, and one each in Odisha and West Bengal.

While sporadic attacks on Christmas carol singing had been reported in previous years, 2025 saw a more coordinated and aggressive pattern of assaults on Christmas-related events and celebrations. In Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, a Christmas feast organised for visually impaired children at a church was disrupted by a local leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The individual, identified as Anju Bhargava, district vice president of the BJP, was reportedly involved in physically assaulting a visually impaired woman and issuing threats, while alleging that forced religious conversions were taking place. Witness accounts indicate that verbal abuse accompanied the assault.

In Delhi’s Lajpat Nagar area, individuals allegedly affiliated with the Bajrang Dal were reported to have harassed women and children wearing Santa caps in public spaces, accusing them of engaging in religious conversion activities. Similar patterns of intimidation were reported in Uttarakhand and Kerala, where Hindu right-wing groups issued threats to schools and hospitality establishments warning against organising Christmas celebrations.

Collectively, these incidents indicate a widening scope of anti-Christian violence in India, characterised by heightened vigilance over religious practices, increased interference in cultural and religious celebrations, and the normalisation of coercive actions under the guise of preventing conversions. This trend raises serious concerns regarding the protection of minority rights, freedom of religion, and the role of the state in ensuring equal citizenship.

The monitoring also flagged the continued lack of accountability for Hindu right-wing vigilante groups, noting that impunity remains a significant concern. According to the report, this environment has contributed to sustained fear and insecurity among minority communities, even in the absence of widespread riots.

At the same time, CSSS observed an increasing hyper-visibility and assertive dominance of Hindu religious festivals, symbols and practices in public spaces. The report argued that this trend reinforces majoritarian cultural hegemony and further deepens social polarisation.

In its assessment, the organisation concluded that while headline indicators such as riot numbers show improvement, the underlying drivers of communal and religion-based hostility remain firmly entrenched. The report warned that without addressing discrimination, hate speech and accountability gaps, the decline in riots may not lead to long-term communal harmony.

Here is Full report prepared by CSSS Team comprising Irfan Engineer, Neha Dabhade & Diya Padalkar

According to the monitoring of Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, the number of communal riots halved in India in the year 2025 as compared to the year 2024. Number of communal riots in 2025 decline to 28 incidents as compared to 59 in 2024, amounting to a decline of 52 percent. However, there was a marginal increase in mob lynching – 14 incidents in 2025, claiming eight lives. Despite the decrease in communal riots, there doesn’t seem to be any respite in identity-based conflict and religion-based hatred, which has taken a different route.

These include institutionalised discrimination against Muslim and Christian communities, the proliferation of hate speech, forced invisibilization and marginalisation of Muslim and Christian cultures from public spaces, and persistence of impunity for Hindu right-wing vigilante groups. Simultaneously, there has been a marked hyper-visibility and assertion of dominance of Hindu festivals, symbols, and practices in public spaces, reinforcing majoritarian cultural hegemony.

Recent attacks on Christmas celebrations in multiple regions of India, reportedly perpetrated by Hindu right-wing groups, as well as sustained campaigns targeting Muslim rulers of the yore and places of worship of minorities, serves as an indicator of communal hostility. Together, these developments underscore a shift from episodic communal riots toward more systemic and normalized forms of communal exclusion and violence.

The year 2025 witnessed a significant escalation in incidents of violence targeting Christian communities across various regions of India. According to data compiled by the United Christian Forum (UCF), a total of 706 incidents of violence against Christians were recorded nationwide as of November 2025. A majority of these attacks were carried out under the pretext of preventing religious conversions, reflecting the growing instrumentalisation of anti-conversion narratives to legitimise coercive and violent actions.

One recurrent and particularly severe form of violence reported during the year involved the denial of burial rights to Christians, especially in tribal-dominated states such as Chhattisgarh. In several instances, state authorities were implicated in the exhumation of Christian bodies, constituting a grave violation of religious freedom and human dignity. UCF documented 23 burial-related incidents in 2025, of which 19 occurred in Chhattisgarh, two in Jharkhand, and one each in Odisha and West Bengal.

While sporadic attacks on Christmas carol singing had been reported in previous years, 2025 saw a more coordinated and aggressive pattern of assaults on Christmas-related events and celebrations. In Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, a Christmas feast organised for visually impaired children at a church was disrupted by a local leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The individual, identified as Anju Bhargava, district vice president of the BJP, was reportedly involved in physically assaulting a visually impaired woman and issuing threats, while alleging that forced religious conversions were taking place. Witness accounts indicate that verbal abuse accompanied the assault.

In Delhi’s Lajpat Nagar area, individuals allegedly affiliated with the Bajrang Dal were reported to have harassed women and children wearing Santa caps in public spaces, accusing them of engaging in religious conversion activities. Similar patterns of intimidation were reported in Uttarakhand and Kerala, where Hindu right-wing groups issued threats to schools and hospitality establishments warning against organising Christmas celebrations.

Collectively, these incidents indicate a widening scope of anti-Christian violence in India, characterised by heightened vigilance over religious practices, increased interference in cultural and religious celebrations, and the normalisation of coercive actions under the guise of preventing conversions. This trend raises serious concerns regarding the protection of minority rights, freedom of religion, and the role of the state in ensuring equal citizenship.

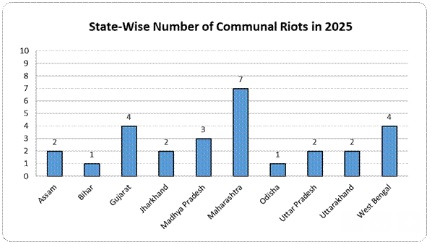

According to monitoring undertaken by the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS), based on reports published in five Mumbai editions of The Indian Express, The Hindu, The Times of India, Sahafat, and Inquilab, the 28 recorded incidents of communal riots in 2025 resulted in four fatalities and injuries to 360 individuals. Of these 28 incidents, seven occurred in Maharashtra, accounting for 25 per cent of the total number of communal riots documented during the year. Furthermore, nine of the 28 incidents were triggered during religious processions or festivals, underscoring the continued vulnerability of such events to communal mobilisation.

Before examining the specific dynamics of communal riots in 2025, it is important to situate these incidents within the broader context of institutional discrimination against Muslims in India.

In 2025, the response of the state to communal riots was grossly partial, favouring the rioters from the Hindu community. This was evident in attempts to withdraw criminal cases against the Hindus who were accused of lynching Mohammad Akhlaq in 2015 in Dadri, by the UP Government. The second instance of favouritism towards Hindu rioters was when the Delhi police refused to probe the alleged role of Kapil Mishra, a BJP minister in Delhi government, in the communal riots in 2020 in Northeast Delhi. Delhi police went in appeal against trial court’s order to probe the role of Kapil Mishra and the sessions court set aside a trial court’s order.

Communal Riots and Losses:

The 28 communal riots in the year 2025 claimed four lives – two of Hindus in Murshidabad – Harogobindo Das and his son, Chandan Das and lives of two Muslims – Irfan Ansari in Nagpur riots and Izaz Ansari in Murshidabad. The total number of injured in 2025 according to CSSS monitoring stands 377- 1 Hindus, 2 Muslims, 104 police personnel and 270 unidentified persons. In the previous year 2025, 59 communal riots had claimed thirteen (13) lives. Thus in 2025, the number of deaths has declined.

In four communal, properties of Muslims were unilaterally attacked and vandalized. In Uttarakhand, on November 16, 2025, rumors spread in Uttarakhand’s Haldwani town (Nainital district) that a calf head was found near a school and temple gate. These rumours sparked communal tensions among locals and led to a mob vandalizing Muslim owned shops and properties in the area. The tension escalated quickly with the mob targeting commercial establishments and causing major property damage. In another incident in the state of Uttarakhand, on April 30, 2025, communal riots gripped Nainital town of Uttarakhand after a 12-year-old girl was allegedly assaulted by a Muslim elderly man. An enraged mob went on a rampage ransacking the market as it vandalised shops owned by Muslims and vehicles parked on the roadsides. Stones were hurled at a religious place of worship of the Muslims.

In Uttar Pradesh, on 16 March 2025, a mosque in Hathras district was partly vandalized by a mob. The attack was triggered by communal tension over the alleged abduction and sexual assault of a seven-year-old girl by a 20-year-old Muslim man.

In Maharashtra, on 1st January 2025, the shops and vehicles owned by Muslims were set ablaze by villagers and party supporters of State Minister Gulabrao Patil. Muslims were targeted after a clash broke out between two groups in Maharashtra’s Jalgaon district, after Gulabrao Patil’s driver blew a car horn that irked locals of Paladhi village. A brawl ensued between the villagers and party supporters after which the enraged mob pelted stones and set ablaze shops and vehicles.

Theatre of Violence:

According to the monitoring of CSSS, out of the 28 communal riots, Maharashtra accounts for seven communal riots or 25 percent. This is a trend that continues from the previous two years where Maharashtra had reported most communal riots according to CSSS monitoring. In 2025, Maharashtra had reported twelve (12) communal riots. The continuing higher number of communal riots in Maharashtra could be attributed to the intense polarization and communal tensions caused by hate speeches during the Sakal Hindu Samaj rallies. From 2022, Maharashtra has been witnessing an intense atmosphere of hatred and communal turmoil.

Maharashtra is followed by West Bengal and Gujarat where each state witnessed four communal riots in 2025. The state of Madhya Pradesh witnessed three communal riots. The states of Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Assam and Uttarakhand had two communal riots each. The states of Bihar and Odisha witnessed one communal riot each.

From the above, it is observed that the western part of India – Maharashtra and Gujarat, alone constitute for 39 percent or 11 of 28 communal riots that took place in 2025 according to CSSS monitoring. Eastern India – Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam, Odisha and West Bengal constituted for 10 communal riots out of 28 amounting to 37%. Northern India – constituting of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Uttarakhand, have reported seven communal riots- constituting 25 percent of the communal riots. The South of India reported none.

West Bengal in the last ten years has frequently witnessed communal riots on the occasion of Ram Navami. Additionally, West Bengal is slated for state Assembly elections. This could contribute to the spate of communal riots in West Bengal. Similarly, Assam too is slated for state elections. Odisha which is now ruled by BJP witnessed more communal tensions.

Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, both ruled by BJP, though report lesser number of communal riots according to the data of CSSS, but they continue to account for most incidents of mob lynching and hate crimes. The discourse in these states has been heavily demonized the religious minorities. The state institutions have targeted Muslims and Christians. Staged police encounters are used to injure or kill alleged Muslim criminals. There is an unwritten policy of demolition of Muslim owned properties as a collective punishment on mere allegations of wrongdoings. Mosques and dargahs are demolished, there are calls of social and economic boycott of Muslims from time to time. The Hindu right wing enjoys large degree of impunity in these states. Communal polarization is achieved through these measures even without resorting to communal riots.

Triggers for Communal Riots:

The communal riots in 2025 reflected the contested public spaces in India where the Hindu right and majoritarian state has consolidated its hegemony. With the assertion that India is a Hindu Rashtra and intolerance towards symbols or culture of other religions than Hindu religion, the processions on religious festivals is taken on routes inhabited by Muslims or Muslim places of worship. Music or provocative slogans are raised to provoke the Muslim community and communal riots ensue. In the past few years and in 2025 too, communal riots were triggered in an attempt to destroy or invisibilize the presence of the Muslim community or their cultural symbols. The legitimacy of mosques and dargahs were contested and sought to be demolished. At the same time, processions on Hindu festivals are taken out in a way from routes which has mosques in order to provoke and humiliate the Muslim community. This was with a clear view to demonstrate the hegemony of the Hindu right to provoke and indulge in violence with impunity.

According to the monitoring of CSSS, 9 out of 28 communal riots took place on the occasion of religious processions and religious festivals, constituting of 33 percent of the total communal riots. This is a trend that continues from 2024 where religious processions and festivals accounted as triggers for majority of the communal riots. 26 out of the 59 communal riots were triggered by religious processions or festivals- almost half of the communal riots.

The states where communal riots took place on the occasions of religious festivals were West Bengal, Maharashtra, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Assam and Gujarat.

In Bihar’s Jamui district in Baliyadih village, on 16th February 2025, a religious procession triggered a clash between two communities. Three people were seriously injured. A group of Hindus were returning after chanting Hanuman Chalisa. The clash broke out when the Muslims allegedly attacked the Hindu group with stone and sticks. The situation in the village was tense and police carried out flag marches in the area to ensure peace. Nine people were arrested and police registered a case against 60 unidentified persons. Flag march was carried out at the village as well in Jamui Bazar where the activists of Hindu Swabhiman called for a bandh (close down of commercial and economic activities).

In Jharkhand, two communal riots took place over religious festivals. On 26th February 2025, a communal riot broke out between Hindu and Muslim communities in Hazaribagh district, Dumroan village over decoration on the occasion of Mahashivaratri and setting up the loudspeakers. Stone pelting was observed from both sides, several shops were set on fire, many vehicles were also torched including four bikes, an auto and a car. According to the police, Muslims protested against hoisting the Mahashivaratri flags and installing sound systems at Hindustan Chowk. Arguments between the two communities turned violent and stone pelting started from a nearby madrasa. In response, Hindus too pelted stones on them. Three persons were arrested. It is to be noted that Bihar frequently witnesses communal riots during religious processions.

In another incident in Hazaribaug, Jharkhand on 25th March 2025, stones were allegedly pelted during a Ram Navami procession triggering tension near Jama Masjid chowk. According to the police, the stone pelting started over playing the music system rendering communal songs in high volume near Jama Masjid Chowk around 11 p.m. when a Mangla procession was underway as part of the Ram Navami celebrations.

Another incident on the occasion of Ram Navami took place in Malda district of West Bengal. On 26th March 2025, communal clashes took place in Mothabari in Malda district, reportedly triggered by an incident during a preparatory Ram Navami rally. As the procession passed near a local mosque, participants alleged that firecrackers were thrown in the vicinity of the mosque. This incident escalated tensions, leading to road blockades and confrontations with law enforcement the following day. The situation further deteriorated, resulting in arson, vandalism, and physical attacks. 34 individuals were arrested. No injuries were reported.

In Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri district, on 14th March 2024, the gates of a mosque were allegedly rammed multiple times during a traditional celebration on the eve of Holi. The alleged incident took place in Rajapur village, during the Shimga festival, a Konkani ritual that involves carrying a tree trunk to the Dhopeshwar temple. Instead of simply placing the tree trunk at the mosque’s steps, as is tradition, some individuals forcibly rammed it into the gate. Police booked several youth in this case.

In Madhya Pradesh, on April 12, 2025, communal clashes that took place in Guna at night during a Hanuman Jayanti procession. According to the police, two communities clashed in Guna’s Colonelganj area at around 7.30 p.m. when a Hanuman Jayanti yatra of about 100 people was passing by a mosque. An altercation broke out between members of the two communities over loud music, that led to sloganeering and stone-pelting. 13 people suffered minor injuries in the clashes. 16 people were arrested. A FIR against five identified and over 20 unidentified persons was filed based on a complaint from the local Bharatiya Janata Party councilor – Omprakash Kushwaha, who was among the organizers.

In Assam, on June 8, 2025, communal riots broke out in Dhubri town during Eid celebrations. The communal riot was triggered when suspected cow meat was found near the Hanuman temple. This led to outrage among Hindu locals, sparking protests that rapidly escalated into stone-pelting clashes between communities amid festive crowds. The violence unfolded in the town’s sensitive mixed areas, with mobs hurling stones at shops and passersby, leading to approximately 200 people were injured, including civilians and police. Several Muslim owned shops were attacked and damaged with broken windows and looted goods. No deaths were reported. Over 38 people from both sides were arrested.

In Odisha, on 4th October 2025, communal riots took place in Cuttack city at Haathi Pokhari near Dargah Bazar. Communal clash took place around 1:30 am during a Durga idol immersion procession when participants objected to songs played nearby, leading to stone-pelting between two communities and injuries to about 25 civilians and 8 police personnel, including the Deputy Commissioner of Police. By October 5th, fresh violence broke out during a VHP-called bandh rally in the same area, worsening the unrest with arson attacks on shops and vehicles, further stone-throwing, and attempts to block roads, prompting authorities to deploy additional forces for crowd control. No deaths were reported, but property damage was extensive, including torched establishments and damaged public transport.

In Bahiyal village in Gujarat’s Gandhinagar district, communal clashes took place on 24th September, 2025, during garba event in the backdrop of the “I love Muhammad” campaign. In counter to the campaign, a Hindu man created a whatsapp status which read “I love Mahadev”. These circulating messages igniting arguments that quickly escalated into stone-pelting between two communities at the garba celebration. The clashes led to arson attacks on 4-8 shops and vehicles, with mobs targeting properties in the village center. No deaths or injuries were reported. The police detained around 60 persons. The administration of Gandhinagar undertook demolition of 186 odd properties which were owned by Muslims alleging that they were illegal and belonged to persons who were involved in stone pelting.

Three out of 28 communal riots were over the protests of the Muslim community over the Waqf Amendment Act. These three riots took place in Kolkata and Murshidabad in West Bengal and Silchar in Assam. In Murshidabad, communal riots took place in three areas. On April 8, demonstrators in Umarpur/Jangipur blocked NH-12 and torched police vehicles. On 11th April, demonstrators in the protest against Waqf amendment vandalized shops owned by Hindus, trains, a TMC MP office, and police station. Arson gutted 113 homes in Betbona and Samserganj. And lastly, on 12th April, a mob murdered father-son duo during the protest that turned violence- father Hargobind Das and son Chandan Das were hacked to death at Dhulian in Shamsherganj. A 17-year-old youth Izaz Ahmed Sheikh who sustained bullet injuries in police firing at Suti succumbed to his injuries. Over 120 suspects were arrested.

In 2025, the “I love Muhammad” processions were met with repression by the state targeting the Muslim community. The alleged “mastermind” of these processions were Muslims. In Bareilly, there were clashes between the police and the Muslim community. Two communal riots, one in Madhya Pradesh and other in Maharashtra, took place over the cricket match between India and New Zealand and ensuing celebrations.

Role of the State:

Though the number of communal riots in 2025 has declined as compared to 2024, the targeting of Muslims and the disproportionate impact of communal riots on Muslim community continues to worsen. As observed previously by CSSS, the state, particularly those ruled by the BJP, in the last few years has been intervening on behalf of the Hindu rioters and inflicting maximum damage on the Muslims. This trend continued in 2025 too. In the 28 communal riots, according to the CSSS monitoring, all the communal riots have not unfolded as clashes between two communities necessarily, where the community members have inflicted damage on the properties of each other. Six out of 28 communal riots have been confrontation between the police and the Muslim community. The state has used its institutions to inflict damage on the Muslim community. The following are some of markers which highlight the role of state in dealing with communal riots.

Portrayal of Muslims as Masterminds of Communal Riots:

In several major communal riots in 2025, state authorities constructed and disseminated a narrative—subsequently amplified by sections of the media—that attributed sole responsibility for the violence to Muslims. In official statements, Muslim “masterminds” or “kingpins” of communal riots were invented. This framing was accompanied by disproportionate arrests and coercive police action against members of the Muslim community.

The Nagpur communal riots exemplify this pattern. Prior to the outbreak of violence, Muslim residents had approached the police demanding action against Hindu right-wing groups for the alleged desecration of a sacred chadar during a Shivaji Jayanti celebration. However, state authorities subsequently advanced a narrative that blamed Muslims for instigating the riots and for causing large-scale damage to Hindu-owned properties. Findings from a CSSS fact-finding mission contradicted these claims, revealing that no Hindu properties were damaged and that the only material losses involved the burning of a small number of vehicles. Moreover, the sole fatality during the riots was that of Irfan Ansari, a Muslim. Despite this, the police identified Fahim Khan, a minor local political figure, as the “mastermind” behind the violence. Khan’s involvement was limited to pressing for the registration of a FIR regarding the desecration incident and publicly criticising police inaction. Nevertheless, more than 100 Muslims were arrested in connection with the riots, and Khan remained incarcerated for over four months before being granted bail.

A similar pattern emerged in relation to the protests organised under the banner of “I Love Muhammad.” In Uttar Pradesh, authorities denied permission for the protests, following which violence ensued. Tauqeer Raza Khan, a Muslim cleric, was held responsible for organising the movement and was accused of instigating the unrest. Stringent legal provisions were invoked against the accused, a Special Investigation Team (SIT) was constituted, and two individuals were reportedly arrested following police encounters. In Bareilly alone, the police registered ten FIRs against 180 named individuals and approximately 2,500 unnamed persons, leading to the arrest of Khan, his associates, and dozens of others.

In another instance, the National Security Act (NSA) was invoked following communal clashes in Madhya Pradesh’s Indore district on the night of 9 March 2025, which occurred during a celebratory rally marking India’s victory in the ICC Champions Trophy final. Thirteen individuals were arrested under the provisions of the Act.

The cases of Nagpur and Bareilly illustrate a broader trend observed across multiple regions, wherein Muslims have faced disproportionate state action in the aftermath of communal riots. This includes mass arrests, externment orders, prolonged incarceration without bail, and the invocation of stringent laws, reinforcing concerns about selective attribution of blame and unequal application of state power during communal conflicts.

Demolition as tool for Collective Punishment:

Of the 28 communal riots recorded in 2025, three were followed by the demolition of properties owned by Muslims, ostensibly on grounds of illegality and the alleged involvement of property owners in the unrest. These actions raise serious concerns regarding the use of demolition drives as a punitive measure rather than as a routine administrative exercise.

In Nagpur, the residence of Fahim Khan was demolished despite a stay order issued by the High Court prohibiting such action. Notably, the property was legally owned by Khan’s mother. Additionally, the residence of another accused individual was partially demolished. These actions suggest a disregard for due process and judicial oversight.

In Bareilly, the local administration demolished a garage belonging to Mohsin Raza located adjacent to his residence, asserting that the 12×14-foot structure constituted an illegal encroachment on municipal and drainage land. The garage had existed for approximately two decades. In the same operation, Raza’s resort was sealed, along with Hamsafar Palace, a marriage lawn owned by Haji Sharafat Khan, an associate of Tauqeer Raza Khan. Furthermore, properties valued at approximately ₹150 crore and linked to Khan’s associates were seized by the authorities.

Similarly, in Bahiyal village in Gandhinagar district, 186 commercial structures were demolished by the administration following communal violence that erupted during a garba night celebration in October. The scale and timing of these demolitions, occurring in the immediate aftermath of communal unrest, point to a pattern of collective punishment.

This continuing trend underscores the growing use of demolition drives as a coercive instrument targeting the Muslim community. Such measures not only engender fear and insecurity but also result in substantial economic losses, thereby exacerbating the social and economic marginalisation of Muslims in India.

Selective Convictions and Disproportionate Acquittals

State efforts to ensure expeditious justice in cases involving the deaths of Hindu victims of communal violence merit recognition. However, the absence of comparable judicial outcomes in cases involving Muslim victims raises significant concerns regarding institutional bias and the unequal application of the criminal justice system.

A contrast is evident in judicial outcomes related to different communal riot cases. In the case of Chandan Gupta, who died during the Kasganj communal riots, a National Investigation Agency (NIA) court convicted 28 individuals. In contrast, cases arising from the Muzaffarnagar communal riots witnessed a series of acquittals in 2025. A court in Muzaffarnagar acquitted all eleven accused—Subhash, Papan, Manvir, Vinod, Pramod, Narender, Kishan, Ramkumar, Mohit, Vijay, and Rajender—citing insufficient evidence and the turning hostile of key witnesses. These individuals had been accused of looting and setting fire to the house of Kamruddin, who was forced to flee with his family. Similarly, Binu Singh, alleged to have led a mob during the Muzaffarnagar riots that resulted in the burning alive of Sarajo (35) and a 13-year-old child, and the critical injury of Ramzano, was acquitted by a court in 2025.

Disparities are also evident in the treatment of accused individuals across communal lines. The bail application of Zafar Ali, President of the Shahi Jama Masjid, was rejected in connection with the Sambhal violence of November 2024. The prosecution opposed bail, citing grave charges including unlawful assembly, incitement to violence, destruction of public property, and fabrication of evidence. Conversely, a sessions court in Delhi set aside an order directing investigation into the role of Minister Kapil Mishra in the 2020 Northeast Delhi riots. Mishra’s inflammatory public statements preceding the violence have been cited in multiple independent reports as contributing to the escalation of communal tensions. The riots resulted in 53 deaths and the displacement of hundreds of residents. Umar Khalid, a student, who was arrested by the police for his alleged role in the Delhi riots has been denied bail even after five years in incarceration.

Five Muslim individuals—Joyanuddin Seikh, Abdul Khalek, Nabi Hussain, Habizur Ali, Osman Ali were sentenced to life imprisonment by a special court in Assam for the killing of a Bodo youth during the 2012 Bodo riots in Assam. However, in the case of the Delhi Riots of 2020, a court acquitted six men, Ishu Gupta, Prem Prakash, Raj Kumar, Manish Sharma, Rahul and Amit, who were accused of being part of a riotous mob and charged with arson. A local court in Uttar Pradesh sentenced 9 men- Abdul Hameed, Mohammad Talib, Faheem, Zeeshan, Mohammad Saif, Javed, Soeb Khan, Nankau and Maroof Ali to life imprisonment and awarded the death penalty to Sarfaraz for the murder of Ramgopal Mishra who was shot death in the Bahriach Durga Puja Immersion riot. 13 individuals were sentenced to life imprisonment, eight months after the murder of father-son duo, Harogobind Das and Chandan Das in the riot, that was triggered by waqf amendment protests in Murshidabad.

Taken together, these developments raise serious questions about the impartiality of state institutions in addressing communal violence. The pattern suggests that communal unrest is increasingly utilised as a mechanism for the prolonged incarceration of Muslims, while simultaneously reinforcing a culture of impunity for actors associated with Hindu right-wing groups. Such differential application of criminal law represents a subversion of the principles of justice and equality before the law, undermining public confidence in democratic institutions and the rule of law.

Mob Lynching:

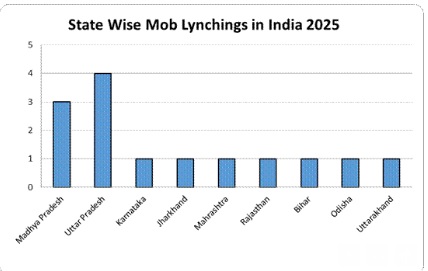

According to the data of CSSS, 2025 witnessed fourteen (14) mob lynching. The 14 incidents of mob lynching claimed eight lives – all Muslims. 14 were injured. Two triggers emerged as most prominent- cow vigilantism which works mostly as an extortion racket and allegations of “love jihad” or interfaith relationships. Other triggers included allegations of theft, suspicions of illegal immigration, raising alleged pro-Pakistan slogans and refusals to chant “Jai Shri Ram”.

As compared to thirteen (13) mob lynching in 2024 according to CSSS data, in 2025 the incidents of mob lynching stand at 14, registering a marginal increase. It is noteworthy that in the recent years, the number of mob lynching has declined. This overall decline can be attributed to the Supreme Court guidelines.

Out of 14 incidents of mob lynching, majority- four (4) took place in Uttar Pradesh and three (3) in Madhya Pradesh. They were followed by one each in Maharashtra, Uttarakhand, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Odisha and Bihar.

Role of the State:

As in previous years, the role of the state in incidents of mob lynching has remained deeply problematic on multiple fronts. State responses have frequently been marked by indifference, delayed action, and, in certain cases, apparent collusion with perpetrators. These shortcomings have significantly undermined accountability and justice for victims.

A particularly egregious instance occurred in Mangaluru, Karnataka, where a mob lynching resulted in the death of Mohammad Ashraf, a 39-year-old rag picker reportedly suffering from mental health issues. Ashraf was assaulted by a mob of more than 30 individuals. Despite the severity of the crime, the police initially refused to register a First Information Report (FIR) for murder, instead categorising it as an “unnatural death”. It was only after sustained pressure from civil society organisations and the release of a fact-finding report by the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) that the police re-registered the case under appropriate provisions relating to murder. The police justified their initial inaction by alleging that Ashraf had raised the slogan “Pakistan Zindabad,” a claim strongly contested by his family, who asserted that he was incapable of articulating such slogans. Both the family and civil society groups have expressed serious concerns regarding the quality and integrity of the police investigation, describing it as inadequate and procedurally flawed.

More broadly, the state has failed to adopt swift and decisive measures to address violence associated with cow vigilantism and extortion networks operating under the guise of cow protection. Rather than curbing such activities, state action has often resulted in the criminalisation of Muslim victims through the invocation of laws purportedly aimed at preventing cattle smuggling or the consumption of beef. A recent attempt by the Uttar Pradesh government to withdraw prosecution against individuals accused of lynching Mohammad Akhlaq represents a particularly troubling reversal of justice. Such actions not only deny accountability in specific cases but also risk establishing a precedent that legitimises impunity in crimes linked to cow vigilantism.

Collectively, these patterns highlight systemic failures in state responses to mob violence and underscore the urgent need for impartial law enforcement, accountability mechanisms, and institutional reform to protect vulnerable communities and uphold the rule of law.