Last Updated on January 27, 2026 9:56 pm by INDIAN AWAAZ

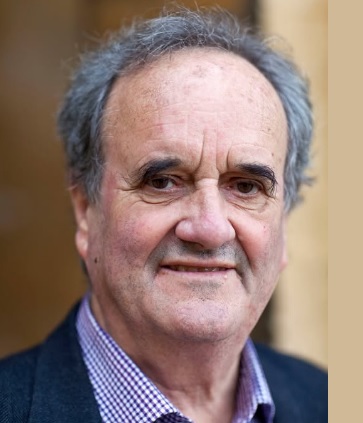

AJ Philip

One of the most frequently voiced complaints against the British is that they came to India as traders, became rulers, looted the country, and left—lock, stock, and barrel. It is a charge often made with historical justification and emotional force. In contrast, the Mughals came, settled here, ruled the land, and made their empire one of the largest and most prosperous the world had seen. Yet history, like life, allows for exceptions. One such remarkable exception was Sir Mark Tully.

Born in Calcutta in 1935, initially educated in Darjeeling, and emotionally anchored to India, Mark Tully chose to remain Indian in spirit long after the British Raj had packed up and departed. He lived in India for most of his life and, fittingly, died here too—on the eve of Republic Day, 2026. That alone tells a story. What makes it even more remarkable is that this was a man who was expelled from the country not once, but twice, during the 1970s. Yet, there was hardly any foreigner who was more Indian than Mark Tully.

His credibility was such that when news reached Rajiv Gandhi—then campaigning in West Bengal—through Intelligence Bureau sources that Indira Gandhi had been assassinated, his first instinct was not to check All India Radio or the Voice of America. He checked the BBC. By then, Mark Tully had become almost synonymous with the BBC in India.

As the BBC’s Bureau Chief in New Delhi from 1972 to 1993, he represented everything virtuous about radio journalism: accuracy, balance, restraint, and a profound moral seriousness. His deep, measured voice during critical broadcasts became the nation’s trusted narrator through moments of crisis—the Emergency, Operation Blue Star, the assassination of Indira Gandhi, and the Bhopal gas tragedy.

The late Khushwant Singh once remarked that he began his professional day by listening to the BBC’s special half-hour morning bulletin around 8:15. That was endorsement enough. I followed suit. When I later attended editorial conferences at The Hindustan Times, I often found myself more up to date on national and international affairs than many of my colleagues. Such was the reach and reliability of the BBC under Mark Tully’s stewardship.

He cultivated a team of stellar Indian reporters and insisted on a journalism that was meticulous, contextual, and free from sensationalism. The BBC’s Hindi Service, in particular, enjoyed an extraordinary following in India, from farmers in Punjab to bureaucrats in Delhi. People treated its broadcasts almost as gospel truth, a testament to Tully’s unwavering commitment to factual integrity.

Naturally, Mark Tully became a cult figure. His writing, too, had a sharp observational wit and a deep empathy for the Indian condition. I vividly remember a piece he wrote on the Ambassador car—British in origin but thoroughly Indian in experience. He observed that every part of the vehicle rattled, squeaked, or groaned, making a sound except the horn. It was a metaphor, he suggested, for India itself: endlessly noisy, resilient, and somehow moving forward despite itself. Even today, the memory makes me laugh.

Do I need to say that I was a fan? When his book No Full Stops in India was published, I bought it immediately and read it cover to cover. It was a revelation. Tully moved beyond the headlines to capture the complex, chaotic, and spiritual pulse of the nation.

What particularly surprised me was a pen portrait of a Bihar politician. Journalists like me usually cultivate a healthy disdain for politicians, whom we often regard as a necessary evil. But Tully broke that stereotype when he wrote glowingly about Digvijay Singh, who represented Muzaffarpur, Hajipur, and Vaishali in the Lok Sabha successively from 1952. Tully painted him not as a caricature, but as a dedicated public servant deeply connected to his soil—an image at odds with the prevailing narrative.

Around that time, Mark Tully visited Patna, possibly to promote his book. On appointment, I met him at a star hotel. It was his partner, Gillian Wright, who opened the door. Since they were staying in a suite, we chatted in the sit-out while he finished his bath. He emerged, a towering figure with a gentle demeanour, and answered all my questions with immense generosity. He spoke slowly, thoughtfully, and suggested that to understand the India he wrote about, I should meet Digvijay Singh at Muzaffarpur.

I subsequently wrote a piece on Mark Tully in my weekly column, In Retrospect, in The Hindustan Times. Soon after, acting on his tip, I visited Digvijay Singh and interviewed him for the same column. He turned out to be erudite, deeply knowledgeable about statecraft and electoral dynamics.

Today, my friend Nalin Verma researched and confirmed that Singh was a scion of the Dharhara estate and had, in a remarkable act of philanthropy, donated 500 acres of his ancestral land to establish Langat Singh College, known as LS College, at Muzaffarpur. This connection, sparked by Tully’s insight, opened a new window onto Bihar’s history of landed gentry turned nation-builders.

Through that connection, I also became friendly with Singh’s brother-in-law, Dr. R.P.N. Singh, head of the psychiatry department at Patna Medical College. A brilliant and eccentric man, he could quote the latest psychiatric texts as effortlessly as Desdemona’s lament.

His eccentricities were legendary; he famously fed his pet monkey liquor until it developed a dependency and had to be shifted to the Patna Zoo—where he ensured that it continued to receive its regular dose of Scotch. These were the rich, human textures of India that Tully had an uncanny knack for discovering and celebrating.

After I shifted to Delhi in 1990, I had more opportunities to interact with Mark Tully. What stood out consistently was his fundamental respect for journalists—any journalist. It did not matter whether one represented The New York Times or Janayugam of Kerala. He treated everyone with equal courtesy, patience, and seriousness. In an era of growing media hierarchies and snobbery, this democratic spirit was rare and refreshing. He believed every story mattered if it mattered to people.

One memorable experience was when we were both invited to a seminar at Aligarh Muslim University. The Vice-Chancellor, who had earlier served in the U.S., introduced us to the Controller of Examinations, who later herself became a Vice-Chancellor. We stayed at the university guest house. After an early dinner, I suggested a visit to the famed Maulana Azad Library. It was past 9 PM, but the vast reading hall was alive—with students sleeping on desks, others buried in books, some copying notes—all wrapped in a profound, pin-drop silence. The collective intensity of aspiration was palpable.

Word reached the librarian, who came to receive us. I mentioned my long-held wish to see Max Müller’s 50-volume Sacred Books of the East. He led us to an entire shelf dedicated to the collection—the very volumes through which the West first systematically encountered the Vedas, Upanishads, and other sacred Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain texts. Muller, ironically, never visited India, yet his work built a bridge. Then came the surprise.

The librarian said he could show us something even more valuable. He returned, carefully placing in our hands a Nobel Medal. It belonged to Dr. Abdus Salam, the Pakistani physicist and Nobel laureate in Physics (1979). Salam, one of the founders of modern theoretical physics, was an Ahmadiyya Muslim ostracised in his own country, which refused to honour him.

Aligarh Muslim University, his alma mater, had become the proud and poignant custodian of his medal. Mark Tully held it with reverence, his eyes wide. He said he had never seen, let alone touched, a Nobel Medal before. In that silent library, holding the symbol of a genius rejected by his homeland but cherished by his alma mater, we shared a moment of deep reflection on the tragic ironies of South Asian history.

At the seminar itself, I had made a passing but pointed reference to a wonderfully colourful report on the Harare Commonwealth Summit filed by a well-known Malayali journalist. Tully, with his keen ear for the absurd and the human, found it so amusing that, on our train journey back to Delhi, he kept recalling snippets of it with visible delight, chuckling at the idiosyncratic style that captured the event’s essence far better than any straight-laced dispatch.

I met him last at the Khushwant Singh Literature Festival in Delhi. By then, age had slowed his gait, but it had not dimmed the warmth in his eyes or his curiosity about the world. He listened as intently as ever. India had honoured him with the Padma Shri in 1992 and the Padma Bhushan in 2005, but his true honour was the trust of the Indian people.

Born to British parents, born in India, living most of his life in India, and dying in India, Mark Tully gave Indians his unwavering love, clear-eyed understanding, and a listening ear—and Indians returned it in full measure.

He leaves behind an enduring literary legacy—books like No Full Stops in India, The Heart of India, and India’s Unending Journey—and an enormous body of reportage that chronicled India not as an outsider dissecting a subject, but as a participant-observer sharing a journey. His work is a masterclass in seeing the universal in the particular, the profound in the mundane.

In remembering Mark Tully, India remembers far more than a distinguished journalist. It remembers a rare friend who, in his own words, learned that in India “there are no full stops.” It remembers a voice that always listened before it spoke, sought to understand before it judged, and in doing so, became an indelible part of the nation’s own story. He was, in the truest sense, the most Indian of British journalists.

Author can be contacted at [email protected]