Last Updated on October 4, 2024 10:00 pm by INDIAN AWAAZ

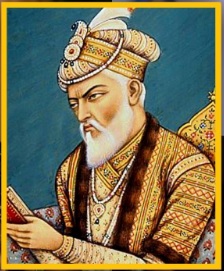

Aurangzeb was neither a hero nor a villain; he cannot be seen in terms of black or white, as he was a complex character, writes Niharika Dwivedi

Niharika Dwivedi

When a Sanjay Raut calls out the Prime Minister’s ‘Aurangzebi attitude’ or when a Modi criticises parties for praising Aurangzeb, it simply reflects Aurangzeb existence in our electoral and national politics. Centuries after, he is still alive in speeches, in debates, in our fascination.

In contemporary politics, Aurangzeb is, as believed by a majority of India, an amalgamation of Hitler and crusader who lived with a sole objective of eradicating Hindus and Hinduism. And so modern-day Indian Muslims are believed to be literal and figurative descendants of Aurangzeb who destroyed India and crushed Hindus. Such ideas rely significantly on V. S. Naipaul’s idea of a ‘wounded civilization’ – the theory that India was subjected to repeated defeats through centuries, including by generations of Muslim conquerors that enfeebled the people and their land. The belief that Muslim invaders destroyed their glorious culture, religion, and homeland is neither a continuous historical memory nor is it based on accurate records of the past. But, for those who subscribe to this view, it comprises real emotional investment. Many in India feel injured by the Indo-Muslim past, and their sentiments—often undergirded by modern anti-Muslim sentiments—drive the contemporary political controversy around Aurangzeb.

However, in history, Aurangzeb was the last effective Mughal emperor who ruled the Indian subcontinent for nearly fifty years. A ruler who is infamous for imprisoning his father, his orthodoxy, and his failure to capture and sustain the Deccan within the Mughal empire. So what does the juxtaposition of modern Indian politics and ancient Indian history connote to? A majority of Indians drifting away from history? From the pursuit of learning the truth? Uncertainty?

What remains certain, however, is the assessment of historians surrounding the personal character of Aurangzeb – his single mindedness of purpose, his dedication to his mission as a ruler, his personal valour and skill as a military leader and his aversion to a life of ostentation.

The point of dispute becomes his motivation. Was his real purport as Sir Jadunath Sarkar in ‘History of Aurangzeb’ suggests the establishment of a truly Islamic state in India which implied the conversion of the entire population to Islam and extinction of every form of dissent?

Or as Pakistani Historian Ishtiaq Husain Querishi argues that in a Muslim state power must be retained firmly in the hands of the Muslims, and the unity of Muslims who had the ultimate responsibility for the defence of the state maintained by a rigid adherence to the orthodox creed (sharia) It was a crime to lull that Muslims into believing that the maintenance of the Empire was not their prime responsibility. Even more disastrous was the encouragement of the feeling that toleration implied the belief that all religions were merely different, all equally good, of reaching the same God!

For Sarkar, Aurangzeb had singly the largest responsibility for the breakdown of the Mughal empire because he alienated the Hindus and expanded the empire till it fell under its own weight. While, for Qureshi, Aurangzeb battled in vain to undo the damage done to the empire by Akbar’s liberal policies and admitting Hindus to the topic services. Ironically, the number of Hindus in the services during the latter part of Aurangzeb’s reign were larger than ever before, rising from 24% under Shah Jahan to 33% in 1689.

Nationalist historians like Dr RP Tripathi have argued that all actions of Aurangzeb were based on political considerations and his apprehension that Hindus had become seditious and were opposing his attempt to establish and strength all-India unity by absorbing in his empire the Deccan as well as the areas dominated by the Marathas.

Both the geographical range and time span implied policies which were often contradictory as well as subject to shifts in view of changed situations.

There is little evidence to show that this led to a wave of temple destruction. It was only in the eighth year of his reign, in 1665, that Aurangzeb ordered it to be destroyed when, as a prince, he had been viceroy of the province but many of which, including the temple of Somnath, had been rebuilt subsequently. The argument of Sakar, followed by SR Sharma, that around this time Aurangzeb issued an order for the general destruction of temples has not been accepted because no copy of any such order has been found. Aurangzeb continued to grant land and other favours to non-Muslim places of worship, like the famous temples of Vrindavan or the Sikh shrine at Dehradun. How then must one explain the destruction of the temple of Vishwanath at Banaras? A simple explanation would be that it was an instance of orthodoxy. RP Tripathi’s argument that these places had become centres of sedition finds no contemporary corroboration. It does appear that Auragnzeb had begun to look upon the preservation of prominent temples as a kind of a guarantee of good conduct on the part of the Hindus of the area. Thus, places of worship began to be treated as objects of reprisal in case of misconduct or rebellion. This was particularly relevant to the ruler of Orccha Bir Singh Deo Bundel’s temple at Mathura when Jats of the area rose in rebellion.

Jizyah, poll tax, paid by non-Muslim populations to the Mughal empire that was abolished by Akbar in 1564 was later revived by Aurangzeb in 1679. Sarkar asserts that Aurangzeb’s purpose was the forced conversion of the Hindus by instituting this measure. Though burdensome for the poor, its incidence was too light for the middle and upper classes, being resented more as a mark of discrimination.

His question is if the measure was purely an orthodox measure, why did Aurangzeb wait 22 years before reinstituting it, despite repeated demands by orthodox sections? Nor was the measure merely economic in nature because Aurangzeb had exempted many taxes levied earlier and earmarked the proceeds of jizya for charity.

Chandra, however, suggests in ‘Jizyah and the state in India during the 17th century’ that the measure was both political and ideological in nature. Ideological as it marked out Aurangzeb as an orthodox Muslim King. It rallied the clergy to his side by providing them jobs as amins (collectors) of jizya with the opportunity of extorting gains in the process. Aurangzeb hoped that this would help in rallying the muslim opinion behind him, not only in his conflict with Rajputs and Marathas but even more in his looming conflict with the Muslim Kingdom in the Deccan.

A simplistic explanation that has been put forward is that in a feudal-militarist state, expansion is the norm unless countered by a countervailing force.

Emphasis on Aurangzeb’s religious policy is slowly giving place to a deeper study of socio economic, intellectual, cultural, geographic and political factors. These studies tend to show Aurangzeb as neither a hero nor a villain; he cannot be seen in terms of black or white, for he was a complex character. He was a rigid and unimaginative politician who failed to understand the societal problems at work in the subcontinent and often took recourse to religious slogans in order to meet complex socio-economic and political problems. Thus, Aurangzeb is no longer regarded primarily as an orthodox-fundamentalist, intent on instituting in India a truly Islamic state as he saw it, or a communalist whose narrow, illiberal views timed the downfall of the empire, or one who battled incessantly against forces of disintegration while he tried manfully to establish an all India empire.

We must now begin to see Aurangzeb as a product and shaper of his times. Professor Rezavi of Aligarh Muslim University puts it beautifully, ‘he was a tyrant and an emperor who lived 300 years ago. At the time there was no modern democracy, there was no constitution to guide him. But today we are guided by the Indian constitution and laws of parliament, so how can you duplicate the deeds that were done in the 16th and 17th Century?’

Niharika Dwivedi is a student at The British School New Delhi, who is deeply passionate about understanding the socio-political nuances of colonial history particularly how marginalised communities were impacted by historical events and policies. Niharika’s passion for highlighting underrepresented narratives is reflected in her work, including her award winning documentary Maahtari, which sheds light on the stigmatisation of menstruation in tribal communities in India.