Last Updated on September 3, 2025 3:56 pm by INDIAN AWAAZ

By Shobha Shukla – CNS

When world leaders adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in 2015, they promised a world where “no one is left behind.” At the heart of that commitment were SDG-3 (health and well-being) and SDG-5 (gender equality). But a decade later, as the 80th UNGA convenes in 2025, the writing on the wall is stark: the world is drifting far off course, and fragile gains are being rolled back.

Fragile Gains Under Threat

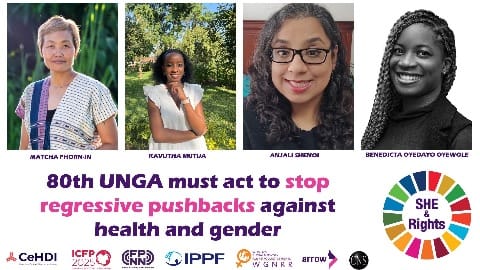

Benedicta Oyedayo Oyewole of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) Africa reminds us that SDG-3 and SDG-5 are not optional add-ons—they are the backbone of the 2030 agenda. “Without them, there can be no human development, no sustainable peace, and no economic transformation,” she warns.

Yet the trendline is deeply worrying. Wars, invasions, genocides, and the rise of anti-rights movements are arresting progress and, in many cases, reversing it. Governments that signed up to protect rights and dignity are instead deprioritising health and gender when it comes to political will, budgets, or cross-sector action.

Accountability Gap

“Governments have a duty to protect human rights of women and gender diverse peoples in all aspects,” stresses feminist leader Matcha Phorn-In from Thailand. “But accountability is missing. Without it, promises mean little.”

She points to how armed conflicts and business interests continue to strip indigenous communities of their land and natural resources—directly fuelling hunger, poverty, and gender inequities. Progress such as Thailand’s Marriage Equality Act, while historic, is an exception rather than the norm in the region.

Africa: Unequal Progress

Africa offers a clear snapshot of both advances and setbacks. Since 2015, some gains have been made in health and gender. Yet, the continent still shoulders 70% of global maternal deaths. In Nigeria, South Sudan, and Chad, women die from preventable causes due to the absence of basic obstetric services.

Conflict-related sexual violence has worsened in South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Somalia. Child marriages remain rampant, robbing nearly 40% of girls in West and Central Africa of education and futures. Meanwhile, universal health coverage lags far below global averages, pushing millions into poverty through out-of-pocket spending.

“COVID-19 and conflicts have reversed some gains,” notes Oyedayo. “But the deeper problem is underfunded systems and political choices that deprioritise women’s health and rights. Every maternal death is not just a tragedy; it’s a blow to national development.”

Policy Rollbacks in Kenya and Beyond

Kenya illustrates how fragile progress can be. Kavutha Mutua, a High Court lawyer and rights advocate, highlights how the country backtracked on comprehensive sexuality education and continues to resist provisions of the Maputo Protocol that safeguard reproductive rights.

These reversals are not isolated. Across Africa and beyond, anti-rights groups are mobilising under the deceptive banners of “family” and “values” to dilute and derail progress. Draft charters such as the so-called “African Charter on Family Sovereignty and Values” threaten to undo hard-won protections. “These groups are even challenging progressive constitutional provisions in court,” warns Mutua.

Asia Pacific: Long Road Ahead

The Asia Pacific region faces its own web of challenges. Rising fundamentalisms, worsening climate change, and economic inequalities have eroded progress. Feminist activist Anjali Shenoi from ARROW highlights that one-third of countries in the region are not on track to reduce maternal mortality, despite it being entirely preventable with accessible antenatal and skilled care.

Femicide is alarmingly high, with the region accounting for 18,100 deaths annually. Up to 64% of women report experiencing physical or sexual violence from partners, and 75% have endured sexual harassment. “These are not just numbers,” says Shenoi. “They are lived realities that demand governments remove barriers to health services and redesign inclusive systems.”

The Cost of Inaction

The economic argument for action is undeniable. The African Union estimates that gender inequality costs sub-Saharan Africa billions in lost productivity annually. Conversely, keeping girls in school, delaying child marriages, and ensuring access to reproductive health services generates long-term economic and social stability.

As Oyedayo puts it: “This is not charity. This is justice. It makes economic sense. The time for political rhetoric is over.”

Investing in Women-Led Solutions

Experts across regions agree: transformative change requires investing directly in women’s rights and community-led organisations. These groups reach the most marginalised—sex workers, people living with HIV, gender-diverse individuals, rural women—yet they receive only a fraction of development financing. Ring-fencing budgets for SDG-3 and SDG-5, ending gender-based violence, and eliminating child marriage must be treated as urgent political priorities.

Countdown to 2030

With just five years left to 2030, the 80th UNGA is a pivotal moment. Activists are calling on governments to halve maternal deaths by 2027, end child marriage within a generation, and guarantee universal access to sexual and reproductive health services.

“We need leaders to deliver, not dither,” urges Oyedayo. “Do not balance budgets on the backs of women and girls. We need courage, financing, and political will to ensure that no woman dies giving life, no girl is forced into marriage, and no one is denied dignity because of who they are.”

The countdown is on. The question for the 80th UNGA is clear: will leaders rise to defend health and gender equality—or will history remember them for allowing regressive pushbacks to steal away a promised future?